Section 1: Q1 2021 Outlook

We Expect an Uneven Recovery and a Prolonged Global Recession

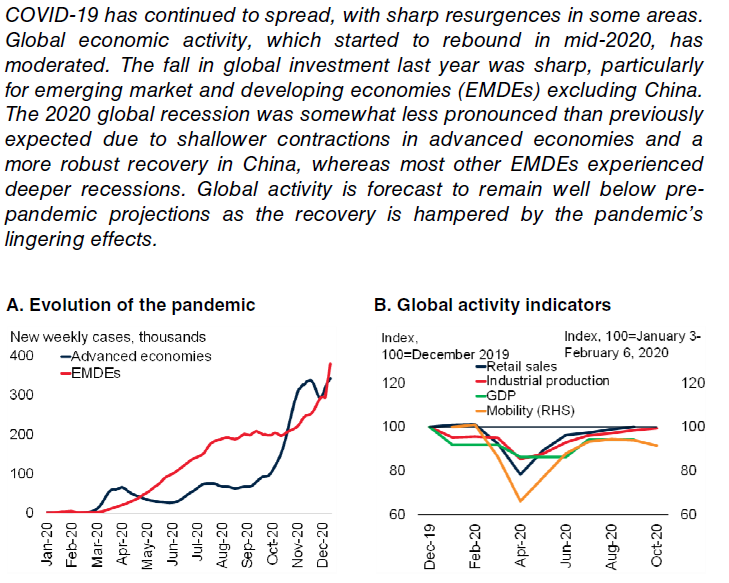

While the world was hoping to see the conclusion of the global pandemic as we entered 2021, instead, we find ourselves more in the middle of the cycle. The pandemic has plunged the global economy into its deepest recession since the Second World War, killing millions and freezing economies across multiple continents. As we enter 2021, there have been over 94 million documented cases of COVID 19 and over 2 million deaths reported globally.i

The impact of weakened fundamental drivers of growth, will steepen the slowdown in labor productivity over the next decade. The pandemic is likely to steepen the long-expected slowdown in potential growth, undermining prospects for labor productivity and poverty reduction. Limiting the spread of the virus, providing relief for vulnerable populations, and overcoming vaccine-related challenges are key immediate priorities.

International bodies, such as the World Health Organization and the Group of Seven, that had been relied upon for a game plan to coordinate a global attack on a global pandemic, proved to be incapable of delivering. Adding to the disaster has been the propensity for the gaps in scientists’ understanding of COVID-19 that have been filled by opportunists.

2020: Teetering Between Recovery and Chaos

From the early months of the pandemic in the spring of 2020, the nature of exponential growth of infections led to a doubling every five or six days. A majority of countries failed to anticipate how they would deal with the spread. Italy’s advanced health-care system collapsed under the burden of cases in March as other countries delayed. Britain went into lockdown two weeks after Italy. During that time infections multiplied between four and eight times. In contrast, Asian countries, such as Taiwan, Singapore, and Vietnam drew on their experience of earlier coronaviruses and acted early and effectively.

Entering April, in response to the global spread, the world underwent a de-globalization as borders closed and travel virtually ceased. And as anticipated, a second wave that was more rampant than the first wave of the virus occurred in the fall. Despite having had months to prepare, governments failed to see the crisis coming for a second time.

Moving forward, the vaccine is a game-changer, allowing restrictions to begin to be lifted. The news of a rollout in record time has brought hope to the situation. The most immediate risk is that the rollout of vaccines is slower than the spread of the virus, held back by bottlenecks in production, or more likely, distribution and administration. As of December 30th, 2.8 million doses of vaccine had been administered in the U.S., a rate at which it will take four full years to vaccinate the entire population. Hopefully this will change as supply chain issues are ironed out and the incoming Biden Administration takes a much more proactive stance. Assuming that there is no virus mutation, by the end of 2021 it is hoped that much of the Western population will have been vaccinated. Western economies can only then begin to return to their long-term trend growth.

Underlying Geopolitical Challenges

2020 saw the deepest global economic setback of the post-war era. Political dysfunction became a way of life in the U.S. and elsewhere. Record joblessness in North America, second and third virus waves, U.S. civil unrest, a near-war with Iran, simmering trade and tech tensions with China, a Russian hack, Brexit uncertainty (again), and an endless U.S. election cycle that then required four days to declare a winner are notable events that followed a profoundly traumatic decade. Underlying challenges were made worse by the economic stress caused by the virus.

• Democracy receded from the heights of the post-Cold War era, retreating in more places than it advanced,

• Brexit and surging populism threatened European integration, one of the defining endeavors of the post-World War II era,

• Globalization encountered fierce political and geopolitical headwinds, as the World Trade Organization become gridlocked,

• China’s economic rise grew more ominous, and

• America became an uncertain advocate of free trade.

COVID-19 is expected to increase global inequality, both within and between countries.

Within countries, the pandemic has hit lower-paid workers particularly hard – the informally employed, women, immigrants, and the low-skilled. Lower-income workers tend to be less able to work from home than higher-income workers and are more likely to be exposed to the pandemic at work and are more vulnerable to job or income losses due to lockdowns.ii The share of lower-paid workers is higher in essential services where workers are more exposed to the pandemic. Social benefits may fail to reach middle income households that have suffered income losses but are outside existing poverty alleviation programs.iii

With regard to inequality between countries, lower-income countries tend to have large informal sectors that concentrate in activities, and operate in facilities, that require close interactions and are particularly vulnerable to pandemic-related disruptions. In addition to causing losses in output levels, the pandemic has set back fundamental drivers of long-term output growth – investment, improvements in education and health, and increases in female labor force participation. Weakening fundamental drivers of growth will be reflected in lower potential growth prospects over the 2020s.

Government Debt and Fiscal Policy Risks

A number of risks related to the pandemic will add to the collateral damage and make the recovery more uneven. These include the rising debt levels in global economies as well as the debt resulting at the corporate level as pandemic related weakness impacts many sectors.

When COVID-19 first began to spread around the world in the spring of 2020, this health emergency risked triggering an economic and financial crisis. America’s financial mechanisms froze as companies scrambled for cash, dumping even their holdings of usually safe Treasuries. Companies and investors the world over rushed into dollars. The bottom fell out of the oil market as demand collapsed. In April the futures price for West Texas Intermediate crude went negative, declining to -$37 per barrel.

As countries locked down, they experienced their deepest downturns in recent memory. But financial panic was averted. The banks stayed resilient. Part of that is a consequence of regulation after the global financial crisis. Fiscal stimulus, government credit guarantees, and central bank action have prevented many losses from occurring. The Federal Reserve stepped into Treasury and corporate-bond markets, a sign of the growing importance of capital markets as a source of credit. The stimulus helped Wall Street, even as Main Street suffered. By August, and again towards the end of the year, the S&P 500 stock market index was hitting record highs. The exuberance was at first concentrated around the sorts of companies, such as those in tech and health care, that did well out of the pandemic. But as news of an effective vaccine broke in early November, it rippled out to emerging markets.

The pandemic has exacerbated the risks to Main Street associated with a decade-long wave of global debt accumulation. Debt levels have reached historic highs, making the global economy particularly vulnerable to financial market stress. There is now almost universal agreement among governments and central banks over the need to maintain fiscal and monetary support until recoveries are entrenched. As a result of sharp output collapses, unprecedented policy stimulus across global economies has led to debt-to-GDP ratios that are set to reach new highs. Global government debt is expected to have reached 99 percent of GDP for the first time on record in 2020.iv

The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to deepen and prolong a slowdown in output, productivity, and investment growth that has been underway for a decade. Weak growth will further increase debt burdens and erode borrowers’ ability to service debt. For some countries in debt distress, the economic outlook may only improve once debt relief via debt write-offs occurs, rather than rescheduling. Pre-emptive debt restructurings have generally been associated with better macroeconomic outcomes rather than restructurings that occur after a default has occurred.v

2020 fiscal easing outstrips 2009 although the amount varies across regions, resulting in divergent growth. Among Emerging Market and Developing Economies (EMDEs), total debt had risen by about 7 percentage points of GDP each year since 2009. In 2020, government debt alone is expected to rise by 9 percentage points of GDP, the most since a series of late 1980s debt crises while corporate indebtedness is also likely to sharply increase.vi

The pandemic has made this wave of debt more dangerous by increasing its risky features. The sheer magnitude and speed of the debt buildup heightens the risk that not all of it will be used for productive purposes. Previous waves of debt have ended with widespread financial crises. When debt resolution was protracted, growth was often slow to recover or even resulted in a lost decade of growth. There is a risk that this fourth wave of debt since 1970, like its predecessors, also ends with a major financial crisis, with some countries already experiencing debt distress.

Since 1970, about half of all countries that experienced a rapid buildup of debt also experienced a financial crisis. Where debt accumulation episodes were accompanied by crises, output and investment were significantly lower even several years after the end of the episode than in countries without crises.vii

A different but related risk is that ultra-loose monetary policies have led to a misallocation of capital that ultimately threatens the stability of the financial system in one or several major economies. This is possible – history shows how a combination of easy money and liberalized capital markets can cause asset price bubbles to inflate, which can then cause economic and financial market dislocation when they burst. This process typically plays out over years. While it is worth keeping at least one eye on China’s property market, we think that the valuation of major asset classes (including equities) can for now be justified in the context of lower interest rates.

Uneven Economic Recovery in 2021

Although the global economy is emerging from the collapse triggered by COVID-19, the recovery is expected to be slow and global GDP is expected to remain below pre-pandemic levels for all of 2021 and 2022. Recessions that feature financial crises are significantly deeper and longer than recessions that do not.viii Against this backdrop, widespread financial crises, combined with a prolonged pandemic and delayed vaccination, could result in a double-dip global recession, with a further contraction in activity this year.

Throughout the second half of 2020, world trade rebounded strongly. The recovery to date has largely played out in the goods economy much more than in services, as consumers can carry on with purchases from home while other activities requiring face-to-face interactions, such as leisure and travel, are more challenging to resume.

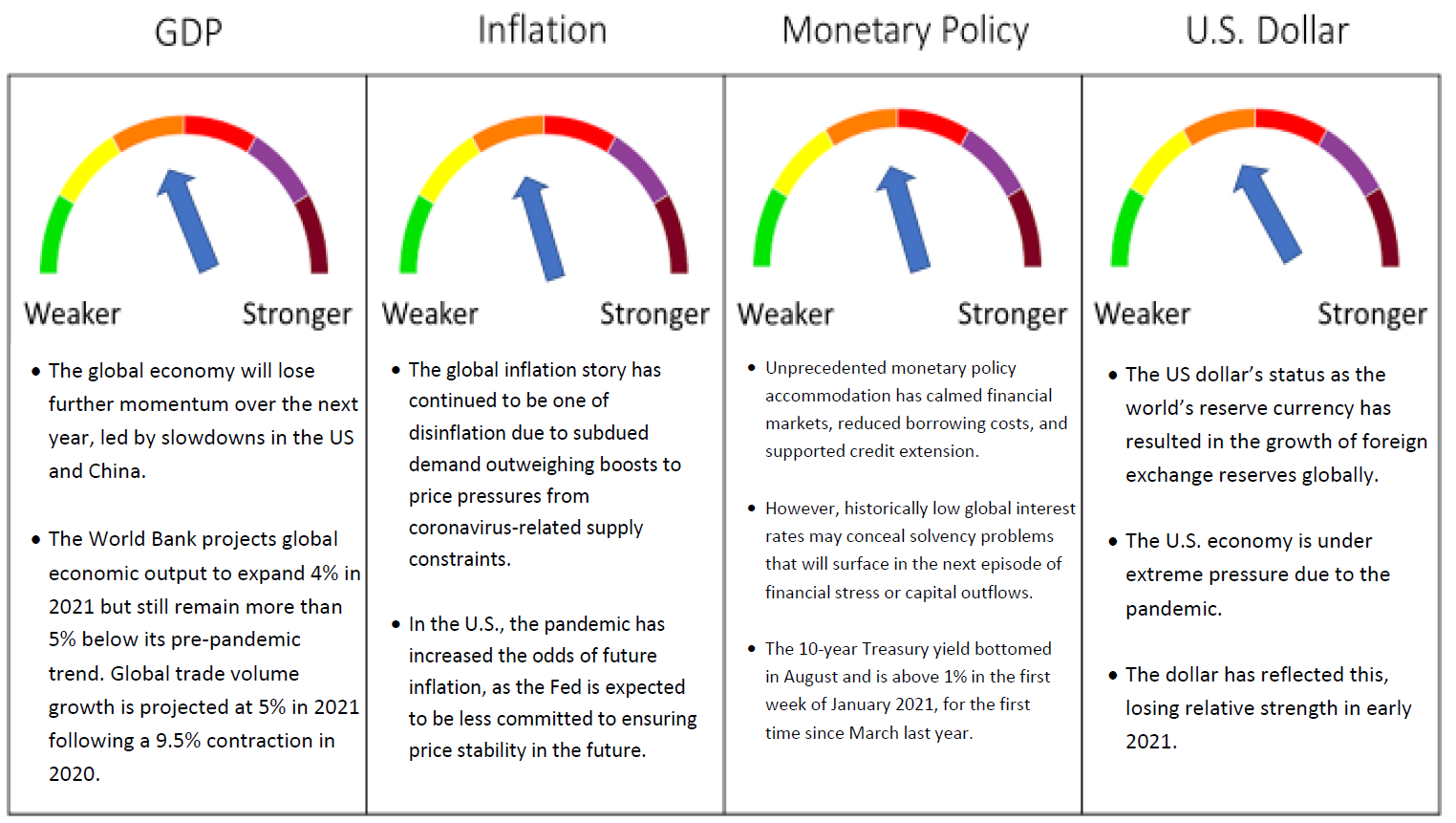

According to the World Bank Global Economic Prospects, published in January 2021, the World Bank projects global economic output to expand 4% in 2021 but remain more than 5% below its pre-pandemic trend. They also project global trade volume growth at 5% in 2021 following a 9.5% contraction in 2020.

Global growth is projected to moderate to 3.8% in 2022, weighed down by the pandemic’s lasting damage to potential growth. In particular, the impact of the pandemic on investment and human capital is expected to erode growth prospects in emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) and set back key development goals.

In the baseline scenario, global output in 2025 would be about 5% below the pre-pandemic trend and there would be a cumulative output loss during 2020-25 equivalent to 36% of 2019 global GDP.

In addition to causing losses in output levels, the pandemic has set back fundamental drivers of long-term output growth – investment, improvements in education and health, and increases in female labor force participation. Weakening fundamental drivers of growth will be reflected in lower potential growth prospects over the 2020s. The World Bank projects global potential growth would slow by another 0.3 percentage points a year compared with pre pandemic trends, to 1.9% a year over 2020- 29, below the 2.1% a year expected before the pandemic.

Global Prospects

SOURCES: COVID-19 COMMUNITY MOBILITY REPORTS (DATABASE); HAVER ANALYTICS; OUR WORLD IN

DATA (DATABASE); WORLD BANK.

Like human capital accumulation, infrastructure investment raises growth directly by increasing the capital stock and indirectly through its collateral benefits for productivity. Good infrastructure investment can raise productivity by improving competitiveness, lowering production costs, facilitating trade, strengthening human capital, and encouraging innovation and knowledge diffusion. For example, better transportation networks can reduce the cost and time of new construction and installation of new equipment, and improved access to electricity and better sanitation can raise educational attainment and public health standards.

The World Bank Global Economic Prospects Report includes two adverse scenarios; one where new infections remain elevated in much of the world, and a second where vaccination delays re-ignite financial stress that spurs widespread corporate and sovereign defaults. Such outcomes could mean just 1.6% growth this year or even another global contraction.

A more prolific pandemic could lead to even larger income losses. In a downside scenario of persistently higher caseloads and delayed vaccination, global output in 2025 would be about 8% below earlier expectations, and there would be a cumulative loss equivalent to 54% of 2019 global output. Delays in vaccine deployment could disappoint financial markets and trigger a repricing of risks. Amid record-high debt, higher borrowing costs could tip many firms into bankruptcy, weakening bank balance sheets, possibly to an extent that could trigger a financial crisis. In such a severe downside scenario, the report projects that global output could contract by another 0.7% in 2021. Cumulative output losses over 2020-25 could amount to 68% of 2019 output globally.

The International Monetary Fund in October slightly lowered its 2021 growth forecast to 5.2%, warning that despite massive stimulus from central banks and governments the world still faces an uneven recovery until the virus is tamed.

Country Level Outlook

The U.S. economy remains stronger than most other global economies. The fall in U.S. activity in the first half of 2020 was nearly three times as large as the peak decline during the global financial crisis, underscoring the depth of the recession. For 2020, U.S. output is estimated to have fallen by 3.6%. Although the pandemic’s economic impact was not as severe as envisioned in previous projections, last year’s contraction was more than one percentage point larger than that of 2009.

Substantial fiscal support to household incomes – far exceeding similar measures delivered during the global financial crisis – contributed to a robust initial rebound in the third quarter of 2020, which was subsequently cut short by a broad resurgence of the pandemic. The 2021 U.S. growth forecast was cut to 3.5% from 4% in June on subdued demand seen in the early part of the year amid new restrictions and a broad virus resurgence.ix

The near-term outlook for other countries including Canada remains clouded by the resurgence in infections and lockdown measures which are weighing heavily on economic activity. While Canada and the U.S. are expected to cross the finish line of 2020 with gains, the Euro area and U.K. economies are projected to contract given more expansive lockdown measures. Substantial monetary and fiscal policy support will underpin modest growth in all four economies in early 2021 with the momentum building as more people are vaccinated, restrictions ease, and confidence improves.

Other highlights from the World Bank report include:

• Euro area projection reduced to 3.6% from 4.5% following stringent lockdowns, with sectors like tourism likely to remain depressed.

• Latin America estimate raised to 3.7% from 2.8% on prospects for restrictions easing, faster vaccinations in the second half, and rising oil and metal prices.

• Many emerging countries had less fiscal room to offer big handouts and as a consequence may suffer greater economic damage.

• Subdued demand and heightened economic uncertainty, combined with disruptions to schooling and employment, are weighing heavily on labor productivity.

Conclusion

The history of the pandemic has been one of hope over experience, with governments anticipating that lockdowns will be short-lived but then retreating as the virus spreads in ways that we failed to envisage.

Policy support from both central banks and governments will eventually lead to the transition to a sustainable recovery. With weak fiscal positions severely constraining government support measures in many countries, it will be a challenge to recover with sustainable and equitable growth.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a global crisis that necessitates a coordinated global response. Only when the pandemic is effectively managed in all countries will individual countries be safe from resurgence, allowing global growth outcomes to improve materially. We expect emerging markets will continue to outpace advanced economies.

Global cooperation is critical in addressing many of these challenges. The global community needs to make sure the ongoing debt wave does not end with a string of debt crises in EMDEs, as was the case with earlier waves of debt accumulation.

Section 2: Four Themes

Theme 1: China

China is on track for its slowest growth since the Mao era, although set against the gloomy global backdrop, economic performance has been exceptional. Structural weaknesses in China’s economy – demographics, rising debt burdens and diminishing returns on investment – are currently being papered over with stimulus.

Growth in China decelerated to an estimated 2% in 2020 – the slowest pace since 1976. It could have been worse but has been helped by effective control of the pandemic and public investment-led stimulus. Accommodative fiscal and monetary policies led to a sharp increase in the government deficit and total debt. Fiscal policy support, which initially focused on providing relief and boosting public investment, is starting to moderate. The recovery has been uneven as import growth lagged a rebound in exports, contributing to a widening current account surplus.

According to the World Bank Report, growth is forecast to pick up to 7.9% in 2021, above previous projections due to the release of pent-up demand, and to 5.2% in 2022 as deleveraging efforts resume. Even as GDP returns to its pre-pandemic level in 2021, it is still expected to be about 2% below its pre-pandemic projections by 2022.

We remain concerned about China’s rising debt and uneven recovery.

Theme 2: Interest Rates

The pandemic led to a global recession as governments shut down large segments of their economies in an effort to slow the spread of the virus. Unprecedented monetary policy accommodation has calmed financial markets, reduced borrowing costs, and supported credit extension. However, historically low global interest rates may conceal solvency problems that will surface in the next episode of financial stress or capital outflows.

At the onset of the pandemic, short-term interest rates fell as central banks reduced short-term policy rates. The Federal Reserve, for example, reduced the federal funds rate (that is, the interest rate that financial institutions charge each other for overnight loans of their monetary reserves) from 1.6% to near zero over a two-week span in early to mid-March.

Long-term interest rates fell as well, as central banks, including the Federal Reserve, made direct purchases of long-term securities and instituted a number of lending programs aimed at maintaining the functioning of financial markets. Additional downward pressure on long-term interest rates came from investors shifting out of risky assets, such as equities, and into safe assets, such as U.S. Treasury securities. Rates were also held down by the fall in demand for investment as firms postponed and cancelled capital expenditure projects.

The 10-year Treasury yield bottomed in August and is above 1% in the first week of January 2021, for the first time since March last year. This follows the Georgia Senate run-off election and an ensuing rise in the chance that the Biden administration passes further fiscal stimulus. The recent rise in rates has effectively been a tightening but the Fed is unlikely to let monetary conditions continue to tighten, as the economy continues to recover. Yields have edged up in the U.K., but not to the same extent as in the U.S. The recovery in risky assets has continued to push down corporate bond spreads, below their pre-virus levels. The next round of fiscal stimulus is expected to assist the state and local government sector. Munis are attractive as a result and have rallied as Treasuries sold off.

The rise in market rates and steepening yield curve is a big plus for financials, especially for the regional banks which will not face any regulatory risk. There is concern over commercial real estate exposure, but that is really a problem that commercial mortgage-backed securities and structured finance players will confront.

We continue to have concerns that asset prices have been driven up by exceptionally loose monetary policy and that they will reverse once central banks start to raise real interest rates back towards their historical levels. At the same time, the equilibrium level of real interest rates is lower than in the past and this is expected to cushion and correction.

Theme 3: Inflation

In general, the global inflation story has continued to be one of disinflation due to subdued demand outweighing boosts to price pressures from coronavirus-related supply constraints. Deflationary pressures from technology are likely to remain muted. Inflation rates are subdued, as they have been for the past decade, but stimulus and demographic trends could prompt a comeback. Higher public debt burden, slower global labor force growth, and the possibility that globalization will be partly reversed, will lead to a gradual rise in inflation over the longer-term. In the near term, with oil prices around $55 per barrel, base effects will ensure a jump in energy price inflation on the anniversary of last April’s collapse in oil prices.

In the U.S., the pandemic has increased the odds of future inflation, as the Fed is expected to be less committed to ensuring price stability in the future. There is no other central bank as openly committed to policy easing as much as the Fed, and no other central bank boosting the monetary aggregates at the same pace. The Fed has stated that it will not touch rates for three more years even if inflation crosses above 2% and the jobless rate drops below 4%. 3% inflation is something the central bank would be fine with. That would imply a prolonged period of negative real rates, which should be bullish for long-duration assets, bullish for hard assets, and bearish for the dollar.

Theme 4: Commodities

Energy and Gold Prices in 2021

Oil prices partially recovered over the second half of 2020 as production fell sharply. This rebound was more modest than the broader recovery in commodity prices as oil demand disappointed while the rise in other commodity prices was mainly driven by strong demand from China. We expect the demand for oil in 2021 to remain subdued and prices to stay within the current range.

Gold was one of the best performing major assets of 2020 driven by a combination of high risk and low interest rates. Given our more cautious outlook for the speed of the recovery, compared to a crypto currency like bitcoin, the risk that gold could go to zero does not exist as there is a floor in its price, because it has physical properties that make it useful even outside of its primary function as a safe-haven asset. Bitcoin, which has marginal intrinsic value, relies on the faith of its holders that it is worth more than nothing and that the technology is sound. We note that the volatility of bitcoin is five times that of gold.

We do not expect to see a strong rebound in energy prices from here but the environment that we have described may result in strong gold investment demand, which could offset low consumption as it did during 2020. We believe there are strong arguments for holding a portfolio that includes hard assets such as gold, things that will keep their value in the face of the ongoing risks that we have discussed in this Outlook.

Section 3. Investment Outlook

Global Pandemic Leads Us to a Recession Forecast for the Next Twelve Months

SOURCE: FRAME GLOBAL ASSET MANAGEMENT

Frame Global Asset Management considers these trends and factors them into our outlook for the economy in our twelve-month forward period. We look back to periods of similar economic behavior and use this information to predict the future behavior of the asset classes that we consider. Our investment process allows us to adapt for non-traditional monetary policy and other exogenous variables.

Section 4. December 2020 Portfolio Models

COVID-19 has wreaked havoc on the world economy, which is set to contract the most since WWII this year as governments shut down large segments of their economies to slow the spread of the virus. There are some signs of recovery as the latest data from the CPB Netherlands Bureau for September showed that real world trade in goods was just 1.5% below its December 2019 level. We have maintained our Recession outlook over our forecast horizon of the next 12 months.

In December, we maintained the asset allocation that was established in November for all models. We continue to favor shorter duration fixed income. With interest rates low or negative, we have maintained exposure to gold. Equity exposure across all models reflects our view that markets are looking through the uncertainty of the pandemic and towards the resumption of more normal life once the population is vaccinated.

We are closing in on the end of a year that introduced the current global pandemic, triggering the deepest global economic setback of the post-war era, record joblessness in North America, second and third virus waves, U.S. civil unrest, a near-war with Iran, trade and tech tensions with China, a Russian hack, Brexit uncertainty (again), and an endless U.S. election cycle that then required four days to declare a winner. The pandemic is unfortunately not over as we enter 2021.

Deborah Frame, CFA, MBA

President and Chief Investment Officer

January 14, 2021

iJohns Hopkins University. National Public Health Agencies. January 18, 2021.

iiWorld Bank. 2021. Global Economic Prospects, January 2021. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi: 10.1596/978-1-4648-1612-3. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO.

iiiWorld Bank. 2021. Global Economic Prospects, January 2021.

ivWorld Bank. 2021. Global Economic Prospects, January 2021.

vWorld Bank. 2021. Global Economic Prospects, January 2021.

viWorld Bank. 2021. Global Economic Prospects, January 2021.

viiWorld Bank. 2021. Global Economic Prospects, January 2021.

viiiWorld Bank. 2021. Global Economic Prospects, January 2021.

ixWorld Bank. 2021. Global Economic Prospects, January 2021.